We Must Hope

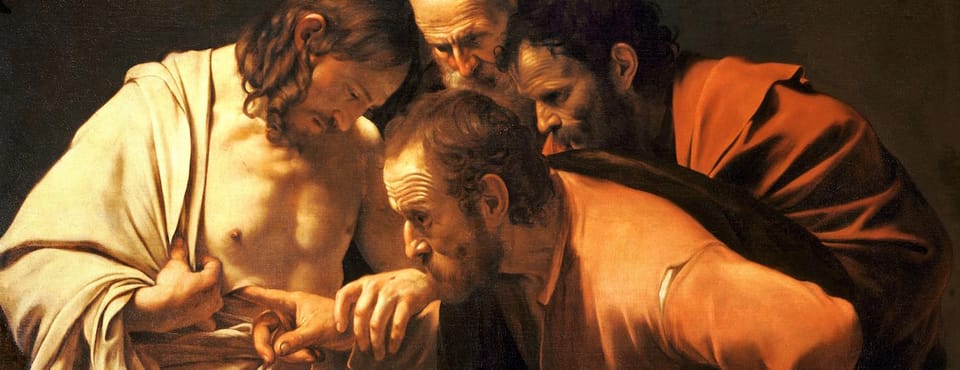

That the Lord came to call the sick and sinners is not news. That He worked miracles, healing all manner of physical ailments throughout the course of His earthly ministry attests to His power and sovereignty over all created things. Yet these miracles, while gifts for those of us who believe without seeing, represent the deeper realities, the deeper mystery of the Incarnation–God made flesh–and the saving message of the Gospels.

The “Good News” for those touched by the Divine Physician was not only a curing of physical maladies, but a two-fold restoration of that person in a manner that only our Good Shepherd was, and is, capable of orchestrating and fulfilling. To be blind, to bear the mark of the leper, to be born or made otherwise physically infirm was, at the time, to be ostracized from one’s community, one’s home. These people, whose faith we have the benefit of knowing and praising via hindsight, existed at the margins; they could not work, could not enter the Temple to praise and worship the God of their fathers. Their dignity was obscured, diminished, forgotten. As Christ sanctifies, or “sets apart to be holy”, the suffering and the sinner were set apart by their fellow men to be cast-off and wretched. Yet Jesus meets them in the depths of their physical isolation and spiritual desolation and says, “Behold, I make all things new.” He takes away their pain, gives them vision, bids them walk on legs previously believed to be cursed, the physical manifestation of sin or evil. He restores them physically so that all the world may know Him and proclaim that He is the Christ, the Holy One of God, and in their healing they find their dignity being renewed and restored. Yet for Our Lord, nothing He did or said should be viewed through a singular or reductive lense, certainly not one that would draw the conclusion that these healings were only physical, only the kindness of a benevolent Creator deigning to give a generation of hard-hearted and spiritually blind people signs and wonders by which they may believe the words of the Prophet Isaiah -”Then will the eyes of the blind be opened and the ears of the deaf unstopped…in the haunts where jackals lay, grass and reeds and papyrus will grow.”

In truth the greatest healing, the true work of Jesus, is in the spiritual restoration of those He touched. With physical bodies now made whole, they are liberated; freed from the shackles of personal and communal isolation they can return to their homes, to their temples, “free to worship God, holy and righteous in His sight, all the days of their life”. Christ’s healing touch is His mercy manifested. It is mercy which heals their souls. And as Christ commands Lazarus and the daughter of Jairus, He commands that dignity be restored to these people, and that we bear witness to that restoration. Like the Father, the Son looks upon His creature, now sanctified, and declares, “It is good.” Truly, there is no greater “good news”.

While these miraculous healings restored the body, and thus the body to the community, they served yet one more even greater purpose. As He desires for all men, Christ has restored the relationship between Himself and the suffering, the sinner. We must recall the lyrics of the Christmas song - “Till He appeared, and the soul felt its worth.” The soul’s worth, obscured as it was, has been realized, called forth like Lazarus. And is this not also the very meaning of the parable of the Prodigal Son? True, the son eventually decides to return to his father’s house and to make amends, but it is the Father who, in his constant watching, sees the wayward son and rushes to embrace him. So it is with our Father in Heaven; constantly watching, keeping vigil for His wayward children to give even the slightest indication that they are on the road home. And, when that sign is given, when the briefest glance toward the Father’s House is perceived, the grace and mercy of Heaven is poured down upon us, precisely because Heaven rejoices far more at the return of the wayward, at the restoration of the sinner who had long-since abandoned his birthright and claim to sonship.

These are not merely theological speculations; they are the reality of the Gospels and the very nature of God, a God whose will, according to St. Faustina, “is love and mercy itself.” So great is God’s love for us that, in healing our physical maladies, He restores us entirely. So constant is His hopeful watching that we have no choice but to accept that in the depths of our darkest days and longest nights, our crown of glory and place in the flock is not far off. We must accept that God’s love and mercy are a mystery to us left behind in this valley of tears, and in doing so we return to Isaiah. “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways” declares the LORD. “As the Heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts.”

We must not relegate Jesus’ miracles to an ancient world; we must believe the author of Hebrews when he says, “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.” We need not look far to find the modern equivalents of the ostracized, the downtrodden, those living on the margins. Truly, Christ tells us that the poor are always with us, and our modern world has reimagined and reincarnated the spiritual poverty of those healed by Christ so long ago. The margins have not changed, but the means by which we place our brothers and sisters there are necessarily different than when Our Lord walked the earth.

We cannot presume to know the mind of God, as the psalmist rightly declares. Truly, we can measure in a thimble our sure knowledge of this world He created. This necessarily means we exist in some measure of uncertainty, and uncertainty for the mind of man is an anxious place, fraught with peril and darkness. Yet the Church tells us that, where there is uncertainty, we must err on the side of Divine Revelation- that God is good, He loves us and has redeemed us. And so, in all things, we hope. We, in fact, must hope if we believe the words of the Creed and the stories of the Gospels. As St. Paul tells us, “Hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts…”

God is often closest when He feels furthest away, lest we forget the words of the Son- “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” At the pinnacle of His incarnation, at His most thoroughly human, Christ speaks these words. Yet just as He continued to sustain Creation while building tables, so too is He accomplishing the mystery of our salvation while His body is nailed to the tree. It is here, at Calvary, that His two natures were closest. In the Garden, in His agony, Christ laments that His soul is “sorrowful, even unto death”- what more succinctly human experience could there be? In Introduction to Christianity, Pope Benedict XVI reflects that Christ's Incarnation, Passion and Death result in a God who becomes so small and so near that we can (and did) kill Him. This Divine Nearness– His sharing in our humanity, in our bitter mortality–is the well-spring of Christian hope and consolatoin.

Member discussion