The Author of Beauty

Wisdom 13:1–9

13:1 “For all men who were ignorant of God were foolish by nature.”

13:3 “…for the author of beauty created them.”

13:9 “For if they had the power to know so much that they could investigate the world, how did they fail to find sooner the Lord of these things?”

While a sunset or sunrise is beautiful to observe, staring directly at the sun leaves us blind. In the same way, when we try to grasp Truth apart from Beauty, our vision falters. Truth itself is not harmful—it is our distorted way of receiving it that blinds us. When Truth is severed from Beauty, our impression of God becomes incomplete and even crushing.

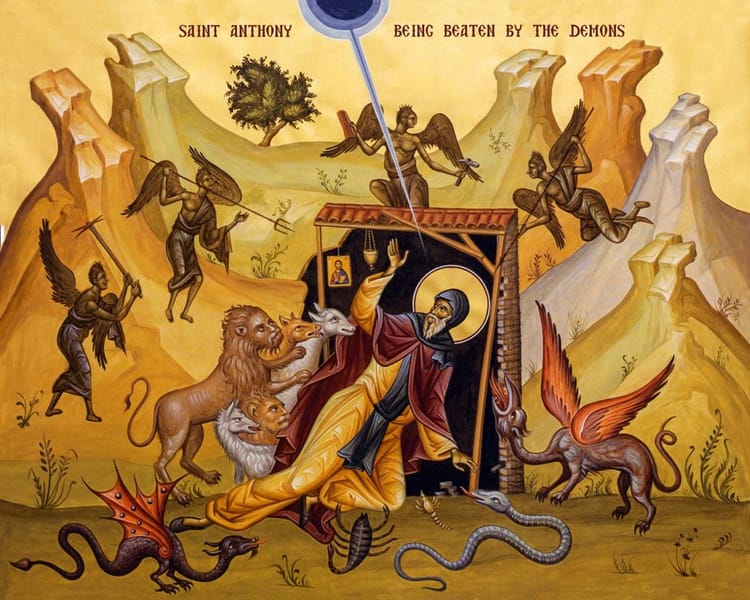

We forget Beauty—that its Author is also the Author of our lives. We forget because this fallen world, this Veil of Tears, forms scales on the eyes of our spirits and callouses on our hearts. And the Enemy gladly fosters both. He does not mind how much Truth we know or even believe in, so long as it is Truth stripped of Beauty, and therefore robbed of its power to set us free.

Augustine’s lament—“Too late have I loved you, O Beauty so Ancient, O Beauty so New”—is the gasp of a soul that sees for the first time that the sun’s intention was not violence against the eyes, but illumination of the world. The Gospel is not meant to blind with God’s Truth, but to reveal that the Beauty of His Truth is the light by which we see everything else.

Yet what of suffering? Where was Beauty in the Garden of Gethsemane or the hill of Golgotha? Where is Beauty when our lives collapse, when the next catastrophe strikes before the last wound has healed? Christ’s answer is as simple as it is profound (as true Beauty often is):

“Behold, I make all things new.” — Revelation 21:5

St. Peter tells us that we will suffer, and St. Paul writes of seeing through a glass darkly. But the Cross does not simply accompany suffering—it transfigures it. In the very place where Truth looks most unbearable and Beauty most absent, they converge. Love shines most brightly where it seems most eclipsed. What appears foolish to the world becomes the wisdom of God: the place where irredeemable things are redeemed, where even death itself becomes a doorway.

Wisdom 13 remarks that he who cannot see God in creation is a fool, and I agree. Who can behold the natural wonders of the world—or hear Bach’s Fugue in D Minor—and fail to recognize that the part of themselves stirred by such Beauty is not self-made, not given by culture, but planted by God? The greater folly, however, is to miss Him precisely where creation seems to break down. This is the scandal of the Cross: that the Author of Beauty was born in a manger, raised in obscurity, and glorified not by worldly triumph but by crucifixion.

It is easy to trace the Beauty of the Empty Tomb once Easter dawn has come. It is far harder to see the Beauty, Truth, and Promise of the Resurrection while standing in the shadow of Golgotha. Yet it is there, at the Cross, that both are revealed most fully, and all things begin to be made new.

Member discussion